In yet another example of the rising emphasis on social media as a political messaging tool, Facebook has this week updated its guidelines in order to make it compulsory for political candidates to disclose any partnerships with influencers who post memes or similar content on their behalf.

On Instagram in particular, Facebook will now require that such arrangements be implemented via Instagram’s Branded Content Ads, which will add a clear “Paid Partnership With” label to these posts.

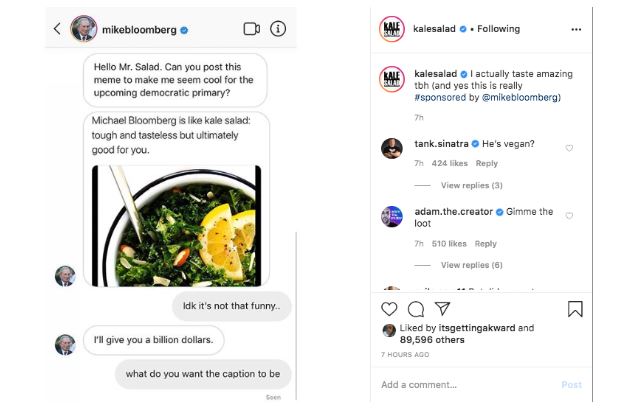

This comes after US Democratic Presidential hopeful Michael Bloomberg partnered with a group called ‘Meme 2020’, which was founded by Jerry Media chief executive Mick Purzycki, in order to commission the creation of memes by various Instagram influencers to help boost Bloomberg’s messaging, and hopefully connect with younger voters.

Bloomberg memes like this have flooded Instagram of late, and many users had been unclear on the motivations behind such. When it was reported that Bloomberg had commissioned their creation, criticism of the individual accounts, and of Instagram, rose quickly, which has now lead to Facebook implementing the new guidelines to provide more transparency.

It’s a questionable tactic – but then again if it works…

Bloomberg, who has a net worth of $62.8 billion (according to Forbes), has reportedly been spending more than a million dollars per day on Facebook ads, on average, over the past few weeks, outpacing all other candidates, including the Trump campaign, which is the next leading political spender on Facebook promotion. The candidates are not outlaying that type of cash for nothing – the massive focus on social media underlines how valuable political campaigners now see the medium, and how much political operatives believe that social platforms can influence voter response.

Of course, we already know that social media can indeed influence voter action, and we know this because Facebook itself has conducted research proving such.

Back in 2010, Facebook said that around 340,000 extra voters turned out to take part in the US Congressional elections because of a single election-day Facebook message. Facebook commissioned a study in which it sent out two variations of a polling prompt to a group of US users – one prompt called on people to get out and vote, while another used the same message, with the added impetus of displayed images of your Facebook friends who had already voted.

The results of the test showed that users who received the informational message (the top message in the above image) voted at a similar rate as those who saw no message at all, but those who saw the social message – with images of their friends included (lower example in above image) – were 2% more likely to click the ‘I voted’ button and 0.4% more likely to head to the polls than the either group.

As noted in the report:

“Political mobilization messages [were] delivered to 61 million Facebook users during the 2010 US congressional elections. The results show that the messages directly influenced political self-expression, information seeking and real-world voting behavior of millions of people. Furthermore, the messages not only influenced the users who received them but also the users’ friends, and friends of friends.”

Back in 2012, Facebook was very keen to tout its capacity to influence voter behavior in this respect, meeting with various political groups to sell them on Facebook ads, often using the above study as a reference point. But after the 2016 US Presidential Election, and the revelations of how Facebook’s audience targeting tools may have been used to manipulate voters, Facebook CEO dismissed the suggestion, saying that:

“The idea that fake news on Facebook, which is a very small amount of the content, influenced the election in any way – I think is a pretty crazy idea. Voters make decisions based on their lived experience.”

To be fair, Zuckerberg was talking about fake news specifically in this instance, but the last line, referring to ‘lived experience’ is particularly dismissive of Facebook’s potential to influence – which, given the above study, and several others like it, Zuck would know is not true.

Facebook has since changed its tune on this, and has been working to implement new measures to ensure that is platform is not weaponized for political gain. But the fact that candidates are spending a million dollars a day on Facebook ads shows that even if Facebook doesn’t want to believe it has the capability to decide who wins elections, campaigners do.

If you’re not taking the potential influence of social platforms seriously in this respect, you’re likely not paying attention.

As such, the new regulations on political memes and influencer partnerships make sense – though it’ll be interesting to note just if and how effective this approach ends up being either way. Without this enforced disclosure, I suspect memes could have more significant influence than people realize – but with the ‘paid for’ tags, they’ll likely lose credibility, and relevance, making it a significant change.

NOTE: In response to questions from journalists, Facebook has confirmed that influencer posts like this will not go into its Ad Library, while Facebook will only fact-check these posts if they are posted in the voice of the influencer, as opposed to the politician paying for the post. Clear? Solid? Good.

Follow Andrew Hutchinson on Twitter